2025-08-18

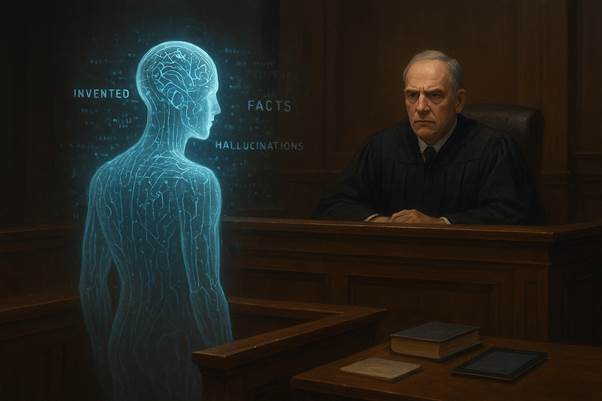

AI in the Dock: When Machines Invent the Law

Welcome to the strange new frontier of artificial intelligence (AI)—a space where machines don’t just make mistakes; they confidently hallucinate. They fabricate legal cases that never happened, create facts that do not exist, attribute judgments to judges who never made them, and cite articles that were never written.

In the age of large language models (LLMs) such as ChatGPT, Claude, and Gemini, AI is no longer just drafting emails or suggesting headlines—it is writing legal briefs, summarising judgments, and even composing contracts. But what happens when it invents facts, and you believe them?

More importantly: who bears the cost when AI lies?

This article examines the legal implications of AI hallucination, the growing risks for practitioners and users, and the evolving regulatory landscape—with a particular focus on Kenya.

What is AI hallucination, really?

In The Executive Guide to Artificial Intelligence – Cutting Through the Hype (2nd Ed.), Andrew Burgess (2nd Ed.) defines AI hallucination as the tendency of Generative AI models, like ChatGPT, to “hallucinate” answers to some questions.

This is brought about by: –

• Lack of True Understanding: LLMs do not fundamentally understand the text they create. Unlike human intelligence, which involves conscious awareness and comprehension, these AI models are “simply parroting” what they have learned from vast amounts of training data.

• Prediction-Based Generation: At their core, LLMs work by working out the patterns in how the words and phrases relate and then predict what comes next. This process is based on patterns and relationships learned from existing data, often comprising the entire internet.

• Seeming Coherence without Factual Basis: The outputs, while often appearing coherent and relevant, can sometimes be fabricated or factually incorrect because the AI lacks genuine understanding of the concepts it is generating. This is considered a potential downside of these powerful models.

In essence, AI hallucination occurs when the model produces plausible-sounding but incorrect information because it is generating text based on learned statistical patterns rather than true comprehension or access to verifiable facts. The book emphasizes that this is a key issue that “could go wrong” with AI and is discussed in detail.

In short, AI hallucination is not science fiction—it is the technical term for when a generative AI system fabricates information while making it sound convincingly accurate. Think of it as an extremely confident intern who has never been to law school—but insists they have!!!

In practice, hallucinations often appear as:

- Citing non-existent case law,

- Misrepresenting case holdings,

- Inventing facts, names, and dates,

- Misstating statutes,

- Falsely attributing statements or documents to real individuals.

These are not mere “glitches.” They are a byproduct of the probabilistic, predictive nature of AI—generating false or fictitious information presented as though it were factual. While powerful, this becomes dangerous without human verification.

How AI can go wrong – The emerging epidemic

United States – Mata v Avianca (2023) 678 F Supp 3d 443 (SDNY)

In 2023, a U.S. lawyer submitted a court brief generated by ChatGPT citing several judicial decisions. None of the cases were real. The court sanctioned the lawyers involved, including a USD 5,000 fine, for relying on false AI-generated arguments.

United States – Morgan & Morgan Law Firm

The country’s largest personal injury law firm filed a motion with eight fabricated citations. Upon discovery, the firm withdrew the motion, apologised, and paid opposing counsel’s costs. They also implemented internal firm policies to prevent such an error from occurring in future. While the court appreciated the steps taken by the firm, it fined the drafting lawyer USD 3,000 and revoked his practising licence and the other signatories were fined USD 1,000 each for breaching Federal Rule of Civil Procedure 11.

United Kingdom – Ayinde v London Borough of Haringey & Al-Haroun v Qatar National Bank [2025] EWHC 1383 (Admin)

In 2025, a first-year lawyer cited five non-existent cases in written submissions. When challenged, she denied using AI. The court, noting her inexperience, declined to cite her for contempt but referred her to the Bar Standards Board for further investigation and appropriate action.

Kenya – PPARB Application No. 72 of 2025: Laser Insurance Brokers Ltd v The Accounting Officer, Nursing Council of Kenya & 2 Others

The Board observed that counsel had relied on non-existent legal provisions and mis-cited statutory sections gave the following warning:

“An advocate’s foremost duty to the Court or any quasi-judicial body is to assist in the fair and just determination of matters before it. This duty is not fulfilled by referencing non-existent laws in an attempt to bolster a client’s case. The pursuit of justice must never be compromised at the altar of persuasive advocacy.”

Legal risks: from mishap to misconduct

- Professional Negligence – Failure to verify AI-generated facts or authorities, particularly in high-stakes contexts, can amount to negligence, attracting disciplinary or civil liability.

- Fraud & Misrepresentation – Using hallucinated material to mislead may lead to contractual disputes, offences under the Computer Misuse and Cybercrimes Act, 2018 (false publication), or claims under the Consumer Protection Act.

- Defamation – False attribution of defamatory statements to a real person is actionable under the Defamation Act.

- Contempt of Court – Misleading the court with non-existent case law or misstated statutes can lead to fines or imprisonment.

Is regulation the right prescription? Insights from Andrew Burgess

In The Executive Guide to Artificial Intelligence – Cutting Through the Hype (2nd Ed.), Andrew Burgess argues that:

- Regulation is the “obvious answer” to AI’s societal risks, including its “million tiny nudges” over time. But regulation is hard because:

- Technology evolves faster than regulators can respond.

- Global consensus on AI rules is almost impossible, leading to watered-down solutions. Examples and challenges noted:

- GDPR (Europe, 2018) – Gives citizens control over their data, requires consent for collection, and restricts certain personal/protected data from AI training—even if this makes models less effective.

- Opacity of AI decisions – In regulated industries, decision transparency is expected; regulators may impose minimum disclosure standards.

- LLM training data – Likely includes copyrighted material; regulators may require disclosure and removal, potentially undermining model utility.

Beyond regulation Andrew Burgess advises:

- Businesses should act responsibly without waiting for the law. “With great power comes great responsibility. Just because you can do something with AI doesn’t mean you have to.”

- Governments can play a role in educating the public about AI- how it impacts them, how to use AI responsibly and what they can do to minimize the harm—Finland’s national AI training campaign is cited as a model approach.

How to Stay Safe: Smart AI Use in Law and Business

Until regulation catches up, if it ever does, risk mitigation is essential:

- Verify everything – Always fact-check AI outputs; liability cannot be shifted to the tool.

- Use trusted legal databases – Kenya Law, LexisNexis, Westlaw.

- Disclose AI use where relevant – Especially in legal, academic, or public contexts.

- Audit your prompts – Keep records for accountability.

- Educate your team – Train all staff on AI’s strengths and limitations.

- Recognise AI’s role – Best for drafting and brainstorming, not for unverified precedent.

- Develop Internal Policies – Define approved AI tools and verification processes.

Burgess advises on some user education and good practices, which include:

- Learning prompt engineering to improve output accuracy.

- Applying human oversight and common sense to validate results.

- Understanding that LLMs predict words—they don’t “understand” information.

Conclusion

AI hallucinations are often subtle—that’s what makes them dangerous. The legal system is built on facts and precedent, not predictions and probabilities.

The next time your AI assistant offers a polished case summary or quote, pause and ask: Did this actually happen—or did the machine make it up?

Because in law, unlike fiction, truth is not optional.

For more insights MMC Asafo Linkedin Articles